The Hierarchy Of Controls

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration, Centers for Disease Control and many other organizations promote a hierarchy of controls to help eliminate or minimize hazards and protect individuals from hazard exposure. The hierarchy of controls is a system that should be used when designing or evaluating processes, such as laboratory procedures. Understanding the controls that are in place and available for use when performing laboratory work or other work that may have potential exposure to hazards is essential. The hierarchy of controls, including examples from the most effective controls, to least effective controls, is as follows:

- Elimination/Substitution (e.g. eliminating the use of a highly toxic chemical in a lab experiment or replacing a highly toxic chemical in a lab experiment with a non-toxic or less toxic chemical)

- Engineering Controls (e.g. Chemical Fume Hoods, Bio-Safety Cabinets, Machine Guards)

- Administrative Controls, including Work Practices (e.g. Lab Policy/Guidelines, Preventative Maintenance, Training, Housekeeping)

- Personal Protective Equipment (e.g. Gloves, Goggles, Lab Coat, Face Shield, etc.)

It takes participation from every level to successfully apply the hierarchy of controls. Individuals involved with the design or review of lab procedures or processes, such as faculty, should evaluate them using the hierarchy of controls. If a hazard cannot be eliminated or substituted, then each subsequent level of control should be reviewed and considered. Engineering controls should be identified and used when available, and should never be bypassed by users. Administrative controls should always be followed by students, faculty and staff. Following lab guidelines, practicing proper techniques in the lab, or even simple housekeeping tasks are all work practices considered to be administrative controls that provide protection from hazards. Personal protective equipment (PPE) is always the last resort. If a hazard cannot be completely eliminated then PPE may still be necessary.

Faculty, staff and students should understand how to use engineering controls and PPE to effectively protect themselves from hazards. They should also have a basic understanding of the limitations of engineering controls and PPE. For instance, some glove materials may not be suitable for use with some chemicals or for use in certain conditions (e.g. incidental contact vs. extended contact).

Glove Chemical Resistance Guide (Fisher)

When working in the lab it is important to understand when the use of gloves is required as well as the appropriate type of gloves to use. Safety Data Sheets should be referenced to help determine the appropriate gloves for each chemical. Additionally, there are a number of chemical resistance guidance documents available online for different types of gloves. Provided below is a Chemical Resistance Guide from Fisher Scientific for latex and nitrile gloves to aid those in choosing a glove for use with specific chemicals.

Container Chemical Resistance Guide

There are a number of guides available online for container chemical resistance. The following link is to Cole-Parmer’s chemical resistance guide: Cole-Parmer Chemical Resistance Guide. The guide allows users to search using three criteria: 1. Material; 2. Chemical; and/or 3. Rating. Faculty, staff and students are encourage to reference chemical resistance guides when using secondary containers for chemicals and when selecting containers for waste.

Secondary Chemical Container Labeling

All containers of chemicals, whether they are hazardous or non-hazardous, must be properly labeled. Unlabeled containers not only pose a serious risk in the lab, they are not compliant with safety regulations. Additionally, unlabeled or unknown chemicals can lead to high disposal costs in order to properly identify or classify the material.

When labeling containers, be sure to remove or deface all previous chemical labels. A container with two or more chemical labels does not effectively communicate the contents! Label all containers clearly and permanently and do not wait until “later” to label chemical containers. Simply put: If you make it, you must label it.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Hazard Communication Standard (HCS) sets forth requirements for primary and secondary hazardous chemical containers. (Click here for more information on HCS). At minimum, HCS requires each secondary hazardous chemical container to be labeled with the Product Identifier or Chemical Name and the Hazards associated with the chemical. The hazards may be communicated using words, symbols, and/or pictograms. The hazards may be found by referencing the chemical’s Safety Data Sheet (SDS) or the primary chemical container. Note that using the most up-to-date SDS is the best option for obtaining accurate hazard information. Although not required, including the chemicals’ concentration, name of individual prepping or transferring the material and the date of preparation or transfer on the label should also be considered.

In laboratory operations, frequent transfer of chemicals from labeled containers to secondary containers (e.g. beakers, flasks, or bottles) is common. Because of this, individuals do not have to label a secondary container if, the material transferred remains under the individual’s possession and is used completely during the same “shift” or lab session. This means that the individual may not leave the area or laboratory without first labeling the secondary container properly. Although an individual may transfer or prepare a material for use over a period of a week, the individual’s “possession” ends when they leave the lab or area for any reason (e.g. lunch, break, meeting, etc.).

Chemical Fume Hood Safety

There are 25 chemical fume hoods in the three buildings that house various laboratories and research areas used by the College of Natural Sciences & Mathematics. The chemical fume hoods are engineering controls that provide additional protection from hazardous and toxic chemicals used in the laboratory. All chemical fume hoods are continuous flow (constant air volume) hoods. All chemical fume hoods are tested annually. Results of the annual testing are posted on each chemical fume hood. Before working in a hood, users should ensure that the fume hood has been tested within the last year. Additionally, the following guidelines will help ensure users’ safety:

- Ensure that the chemical fume hood is operating. If unsure, do not use the hood.

- Concerns or problems should be communicated immediately to department chairs within the SNS&M and the Campus Environmental Safety Coordinator.

- Keep hood sash at proper operating height as indicated by the marking on the side of the hood face.

- Wear the appropriate Personal Protective Equipment (Use of the hoods and their sashes don’t exclude you from wearing PPE! Always follow recommendations in the Safety Data Sheets or from your instructor).

- Do not place head or face in or across the plane/face of the hood.

- For optimal protection, work should be done at minimum of six inches from the face of the hood.

- Close the sash when hood is not in use.

- Do not use the chemical fume hood for long term storage.

- Practice good housekeeping. Clean up spills and debris immediately.

- Do not use perchloric acid in Shepherd University hoods. No hoods on campus meet the requirements for use with perchloric acid.

- Minimize use/storage of items directly in front of the baffles as a build up of materials may restrict air flow, ultimately compromising performance.

Hot Plate And Bunsen Burner Safety

Hot Plate Safety

Hot plates are commonly used in the laboratory and can become a hazard if not managed and used properly. Follow these guidelines to help protect yourself and others using hot plates in the lab:

- Always inspect cords prior to use. Damaged cords must not be used. Never use a hot plate with a missing ground plug, exposed wires, melted insulation, or other forms of damage.

- Hot plates with damaged cords should be labeled to effectively inform others that the hot plate should not be used. Students should notify instructors of damaged hot plates. Faculty should notify department chairs of damaged hot plates.

- Use hot plates in a way that will prevent electrical cords from contacting the hot surface. Never wrap a cord around a hot plate that has not cooled.

- Allow hot plates to cool prior to storing them in cabinets, drawers, etc.

- Inspect glassware for damage prior to using with a hot plate. Damaged glassware, such as cracked glassware, can shatter without warning.

- Clean hot plate surfaces regularly, but only do so when the hot plate is unplugged.

- Unplug and safely remove spills promptly.

- Never use in the presence of flammable materials.

- Do not place metal foil or metal containers on the hot plate.

- Use tongs or silicone rubber heat protectors to removing hot glassware from hot plate.

- Turn off hot plates when not in use.

Bunsen Burner Safety

Bunsen burners are also commonly used in the laboratory and can become a hazard if not managed and used properly. Follow these guidelines to help protect yourself and others using hot plates in the lab:

- Do not attempt to light a Bunsen burner without knowing the proper procedures (see below for procedures on lighting a Bunsen burner).

- Tie back long hair and do not wear loose clothing when working with a Bunsen burner.

- Never use in the presence of flammable materials.

- Never leave a lit Bunsen burner unattended.

- Always shut off Bunsen burners at the valve

Flinn Scientific’s Procedures for Lighting a Bunsen Burner is a good resource for those using Bunsen burners.

Transporting Chemicals Safely

Transporting chemicals from one lab to another or from one building to another should be done with caution. Below is a list of general guidelines for the safe transport of chemicals.

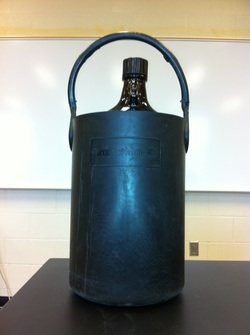

- Transport 2.5 L or 4 L bottles in hand-held safety carriers. Carriers help prevent breakage and also provide secondary containment.

- Chemical containers received by a department may also be safely transported using the DOT approved container in which they were shipped.

- Never pick up or carry containers by their lids.

- Do not attempt to carry an “armful” of chemical containers/bottles. Instead, use a cart or a chemical carrier. During transport, ensure that the chemical containers do not contact or collide with each other.

- Transport high-hazard chemicals during times when there is low traffic.

- When transporting compressed gas cylinders, always use a hand-truck. Cylinders should be capped and strapped to the hand-truck prior to transport. Never drag or roll cylinders. Once cylinders have reached their destination, they should be secured (chained or strapped) in place.